Denon Discovers Ancient Egypt

One of the surprises of the Egyptian expedition was the contribution made by Dominique-Vivant Denon. Denon was a diplomat and artist who had moved his way up in Parisian society, befriended King Louis XV, survived the Revolution, and attracted the attention of Napoleon. He joined the expedition at Napoleon’s invitation, even though he was not included in the Commission of Sciences and Arts. When, in December 1798, Napoleon decided to send General Belliard to join up with General Desaix in pursuit of of the Mameluke leader Murad Bey into Upper Egypt, Denon was the one artist who was allowed to go along. He made good use of his time, sketching furiously when the troops paused for brief moments.

Denon was the first artist to discover and draw the temples and ruins at Thebes, Esna, Edfu, and Philae. Until that time, most of the known Egyptian antiquities were pyramids and scattered pieces of sculptures and stelae. It was when the brigade reached Dendera, just across from Qena, that Denon realized what might be in store. He came through the gate and got a view of the portico and was enthralled.

“I felt that I was in the sanctuary of the arts and sciences…Never did the labour of man show me the human race in such a splendid point of view. In the ruins of Tentyra [the Roman word for Dendera] the Egyptians appeared to me giants.”

He had to move on after less than a day, but he did have time to discover a circular zodiac on the ceiling of a small chapel on the roof of the temple. Drawing it, however, would have to wait.

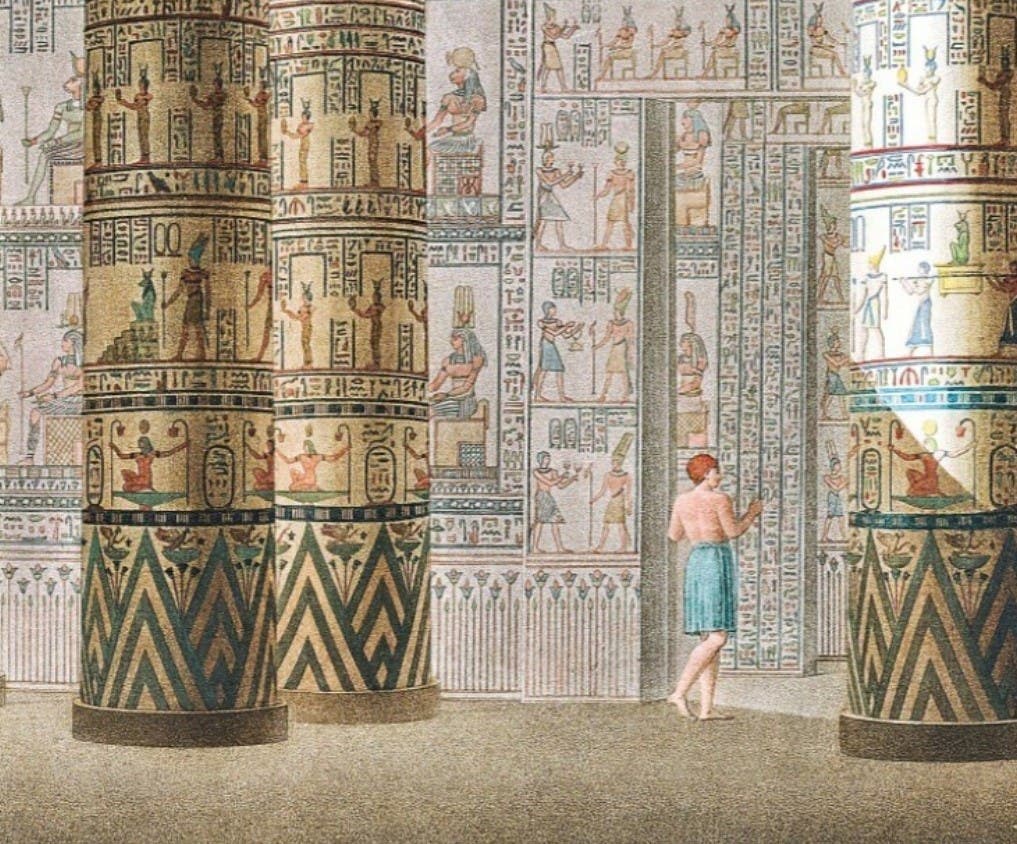

The troops moved south rapidly. They reached Esna, then Edfu, where he saw “the sublime temple of Apollinopolis,” which he later called “the most beautiful of all Egypt.” Denon began to realize that, in architecture, the Egyptians had anticipated the Greeks, and in his opinion, surpassed them. He noted that the capitals on their columns “borrowed nothing from other peoples,” but used the productions of their own country, such as the papyrus, lotus, palm, and reed for ornament. He drew as best and as fast as he could, but every day, at one in the morning, the drums would roll, and they would push south.

By early February 1799, they were at Syene (Aswan), and Denon finally had some time to draw with leisure. He lived on lush Elephantine, the island opposite Syene, just before the first cataracts of the Nile, and saw the Nilometer that Strabo had mentioned long ago. And then he discovered Philae, a small island just a little further up the Nile, which marked the ancient entry point into Egypt. The local inhabitants would not allow the French to land for quite some time, but eventually the natives were forcibly evicted, and Denon got to see the many temples on the island.

“The next day was the finest to me of my whole travels. I possessed seven or eight monuments in the space of six hundred yards, and could examine them quite at my ease… I was alone in full leisure, and could make my drawings without interruption.”

Although the Temple of Isis filled him with awe, he was even more enthralled by the tiny Kiosk of Trajan. He wrote that if ever the French were to take a monument back to Paris, this would be the one, for “it would give a palpable proof of the noble simplicity of Egyptian architecture, and would show, in a striking manner, that it is character, and not extent alone, which gives dignity to an edifice.”

By the end of February, the soldiers headed back north, with Murad Bey always a little ahead of them. Denon thus got a second chance to see many of the monuments, and as the troops doubled back, sometimes a third, but with never enough time to do any site artistic justice. He went through Thebes three times, rushing past the temples of Luxor and Karnac, without being able to draw anything, before he finally, on a fourth visit, was able to record the ruins. And it wasn’t until May that he finally had a chance to revisit Dendera and draw the zodiac, that he would make famous.

Until that time, Denon was alone in his attempts to make visual records of the Egyptian monuments. But in May, he ran into another expedition that had been sent out by Napoleon, under the direction of the engineer Pierre-Simon Girard. The purpose of this expedition was to make a hydrographic study of the upper Nile, and many of the members of the Commission were sent along. Denon showed them his portfolio, which included a view of the magnificent Colossi of Memnon, on the plain west of Thebes. The engineers were amazed, and wanted to spend their time recording groundplans and elevations, but Girard objected strongly. Archaeology was not their mission, he claimed. But whenever their hydrographic work was done, the engineers would head for the ruins.

Denon moved on. After a trip over to the Red Sea, and various other excursions, he finally arrived back in Cairo in July of 1799. He met with the remaining members of the Institute, and showed them his drawings, and they too were captivated. More importantly, so was Napoleon, and he quickly authorized two more expeditions to Upper Egypt, with the express purpose of studying the antiquities. The commissions would head south in August. But not before Napoleon had fled the country back to France, deserting his troops and his savants, and taking with him Monge, and Berthollet, and Denon. Denon, never one to waste time, immediately began to prepare his journal and his drawings for publication. They appeared in a sumptuous folio edition in 1802, and for the first time, readers became aware of the magnificence of Luxor, Karnac, Philae, Edfu, and Dendera. The appetizer was served and the table was set for an even more impressive account of ancient Egypt, the Description de l’Égypte.