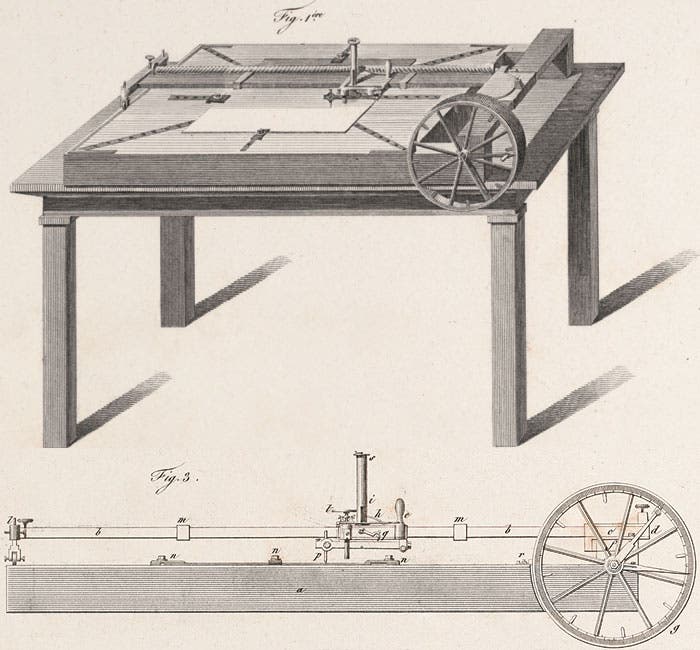

Conté's Engraving Machine

Conté was an ingenious inventor who was noted for his exceptional manual dexterity. “He had all of the sciences in his head and all of the arts in his hand,” according to a saying often attributed to Napoleon Bonaparte.

In addition to being a skilled painter, chemist, and engineer, he was also in charge of the expedition’s balloon corps. In Egypt, he immediately set up a number of industrial shops in the Institute houses, where he made equipment to replace that lost in the sinking of the Patriote. He was also assigned to investigate and collect information on the industrial arts of Egypt, to go into workshops, question the artisans and draw the tools and techniques of the workers.

He produced a series of scenes of various trades and technical processes in Egypt. Eventually these became part of the published illustrations in the volumes of the Description de l’Égypte that deal with the modern state, where we can see into the shops of the miller, baker, distiller, barber, tool-sharpener, and glass blower.

Through his observations and descriptions of the arts and industries of Egypt, Conté was an important contributor to the Description de l’Égypte. He was also appointed Secretary of the Egypt Commission and put in charge of overseeing the publication of the Description de l’Égypte when the French scientists returned from Egypt and began working to publish the results of their work. But without Conté’s invention of a machine to automate and speed up the engraving process, the whole publication might never have been completed. Conté's machine mechanized the engraving process, allowing long, straight, even lines to be engraved more precisely and much faster than humanly possible.

The first edition of the Description de l’Égypte eventually included 837 copperplate engravings, most of them impressively large elephant folios and some of them even bigger, double-elephant folios that were twice as large. A single plate might require hundreds of engraved lines to faithfully portray, for example, the cloudless Egyptian sky. The sky had to appear dark at the top and fade gradually to a pale expanse at the horizon. Engravers did this by varying the depth, width, and distance between the engraved lines that stretched horizontally across the plate. But a single plate could have hundreds of such lines, each of which needed to be uniform along its entire length of nearly two-and-a-half feet. It stretched the limits of human ability, and the time to complete a single plate by traditional methods could be up to six months.

Conté's engraving machine. Image source: Napoleon I, (Edme-François) Jomard, and Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Fourier. Description de l’Egypte.... État moderne text, vol. 2, A Paris: De L’Imprimerie impériale, 1809-1828, Vue et plans de la machine a graver, pl. [1].

With Conté’s machine, the work of engraving the skies and large surface areas took two to three days instead of months, and it could be done with a perfection that only a machine could achieve. Conté’s invention is illustrated at the end of one of the volumes of memoirs in the Description de l’Égypte.

Examples of what the machine could do are included on a sheet that follows — forty-two different techniques that show how the lines could be endlessly varied in patterns of thick and thin, light and heavy, straight and wavy, horizontal and diagonal, and using techniques of etching or drypoint engraving. A close look at the many plates on display from the Description will reveal the amazing success of Conte’s engraving machine.