Popular Perceptions of Dinosaurs

Sprinting Iguanodon, 1927

Gerhard Heilmann wrote The Origin of Birds to offer evidence against Huxley's thesis that dinosaurs evolved from birds (see item 15). Heilmann's primary argument was that the birdlike dinosaurs lacked any evidence of a wishbone or of collar bones, and collar bones are the presumed antecedents of avian wishbones. The book proved very persuasive, and the dinosaur-bird connection was abandoned for many years until it was revived in the 1970s.

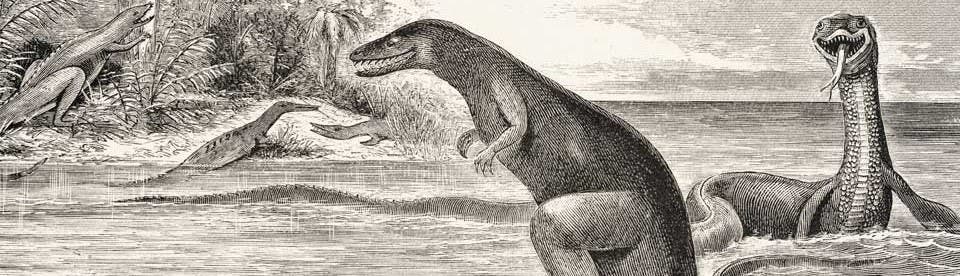

But his thesis didn't keep Heilmann, a talented artist, from representing dinosaurs in very active, birdlike poses. His drawings of Compsognathus, running flat-out with its head down (right), and of a pair of sprinting Iguanodon (below), have become classics, since they seem to embody so well the concept of the active dinosaur.

Most of the illustrations are pen and ink drawings, but the book also includes a double-page wash drawing of the Berlin Archaeopteryx that is absolutely stunning, and is too rarely reproduced.

Struthiomimus and Gorgosaurus, 1927

There are 142 figures in Heilmann’s book, all drawn by Heilmann himself, but only six of these are restorations of dinosaurs (his book, after all, is about birds, which he did not think were related to dinosaurs).

In addition to Iguanodon and Compsognathus, he also depicted Struthiomimus (right) and Gorgosaurus (below). Struthiomimus was named in 1916 by Henry Fairfield Osborn (see item 35), from a specimen discovered by Barnum Brown in 1914. Gorgosaurus was discovered by Charles H. Sternberg in 1913 and named and described by Lawrence Lambe in 1914. Some consider it to be an Albertosaurus; others prefer to retain Gorgosaurus as a separate genus.

Heilmann's Archaeopteryx, 1927

Although Heilmann’s dinosaur restorations are justly renowned today, because he showed dinosaurs in such active poses, those are relatively small images, set right into the text. For his representation of the Berlin Archaeopteryx, Heilmann chose to use a large, double-page, folding plate. In what appears to be a photolithograph, Heilmann reproduced a life-size drawing that he himself had made from the actual specimen in Berlin. The reproduction shows his drawing at one-half size. Although the plate is mounted in the book with the head at the top, it is apparent from the signature that Heilmann drew it with the head at the left, as has always been the convention with this specimen, and we therefore show it here in the conventional position.

For other images of the Berlin Archaeopteryx, see item 16.