Optics: Telescopes and Technological Change

Alessia Tami (University of Zurich)

Sunspots

Sunspots Through the Telescope

By 1609, the development of the telescope suddenly reduced the distance between the Sun and observers on the Earth. The following year, English mathematician and cartographer Thomas Harriot was the first to make an astonishing observation. Dark spots could be seen through the telescope that seemed to appear, move, and even disappear from the Sun’s surface.

Click here to learn more about Thomas Harriot.

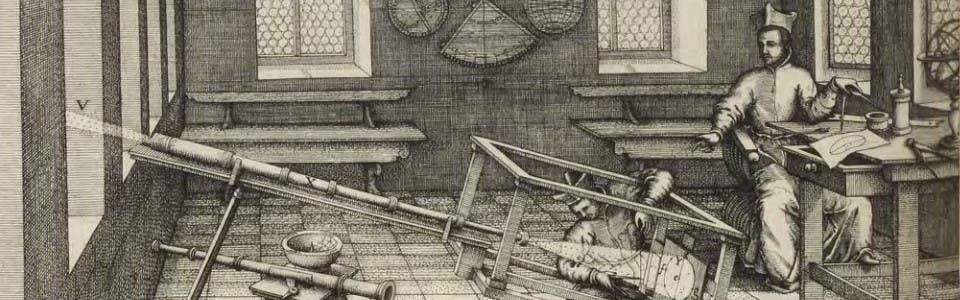

Shortly after Harriot’s discovery, Italian astronomer and physicist Galileo Galilei noticed the same phenomenon. Harriot, Galileo, and the German Jesuit Christoph Scheiner would go on to innovate optical instruments and techniques to record the movement of sunspots. Their works and their rivalry reveal a deep fascination with the Sun.

Click here to learn more about Galileo Galilei.

Click here to learn more about Christoph Scheiner.

Earlier Sightings of Sunspots

Sunspots had actually been observed for many centuries before the invention of the telescope. In Japan, a sunspot was recorded in the Japanese national histories, the Rikkokushi, as early as 851 CE. In China, illustrations of sunspots were added to the Yuánshĭ and Míngshĭ, official imperial histories covering the period from the thirteenth to the seventeenth century.

In the Latin West, however, there had been no tradition of sunspot study, beyond occasional observations recorded in the chronicle of an English monk, John of Worcester that date as far back as December 8, 1128. As a consequence of this “knowledge gap,” European astronomers thought of sunspots as a novel phenomenon.

At the time of their rediscovery in seventeenth-century Europe, telescopic sunspot observations proved that the Sun’s surface was flecked and mutable, forcing a reconsideration of older beliefs that celestial objects were perfect, fixed, and unchanging.

The Modern Physics of Sunspots

Astrophysicists now know that sunspots are lower-temperature areas on the solar disc caused by a strong magnetic field. The largest sunspot clusters can cover several times the size of the Earth, with a lifespan ranging from only a few hours up to several months.

Activity in the Sun’s magnetic field rises and decreases over approximately an eleven-year period known as the Schwabe cycle. The 1610s were characterized by unusually high solar activity, with more than one hundred sunspots recorded.

Between 1645 and 1715, sunspots almost completely vanished from the solar surface in a period of especially light solar activity known as the Maunder Minimum. Telescopic observations by Thomas Harriot, Galileo Galilei, Christoph Scheiner, and many others have left a rich written history of the Sun. Their records provide essential data to solar physicists studying the evolution of the Sun over the last centuries.

The Controversy Around Sunspots

Providing a plausible scientific explanation for sunspots in the seventeenth century required astronomers to take a stance on the form of the universe. In 1612, a dispute erupted between Galileo Galilei and Christoph Scheiner, over their respective solar observations.

In three letters written in 1612 to German astronomer Mark Welser, Galileo argued that sunspots were likely to be either on the Sun’s surface or in its atmosphere, much like clouds on Earth. In the same year, Scheiner also corresponded with Welser, but he instead opposed Galileo’s view. The letters written by Galileo were printed in 1613 under the title Istoria e dimostrazioni intorno alle macchie solari (Letters on Sunspots), alongside a transcript of one of Scheiner’s letters, written under a pseudonym.

Galileo was aware of Scheiner’s divergence in opinion, and in his third letter, he critiqued Scheiner’s theory. At stake in the controversy was the Aristotelian idea of the heavens as perfect and immutable, something Galileo was now calling into question.

According to Scheiner, sunspots were caused by small planets orbiting very close to the Sun. He believed that when one of these planets came between the Sun and the Earth, it would look like a sunspot, only to disappear once it continued on its path.

Likewise, the French vicar and astronomer Jean Tarde initially agreed that sunspots were produced by small planets orbiting the Sun.

Tracking Sunspots

Despite Christoph Scheiner’s initial reluctance to accept sunspots as marks on the Sun’s surface, his Rosa ursina was instrumental in achieving a more accurate understanding of the Sun as we know it today. Based on many years of astronomical observations and meticulous record-keeping, Scheiner discovered that the path followed by sunspots varies with the seasons. He also found that changes in sunspot paths were caused by the Sun’s rotation, over just under a month, from east to west.

Solar Differential Rotation

Scheiner also discovered that the Sun rotates more slowly at its poles than around the equator, a phenomenon that has been termed “solar differential rotation” by modern astrophysicists. Far from being a mere blemish on the Sun’s surface, early modern sunspots gradually revealed to astronomers the Sun’s many changeable features, which would otherwise have remained invisible to observers on Earth.