Eclipses, Comets, and Omens: Older Ways of Reading the Skies

Wilmari Claasen and Olivia Lanni (University of Zurich)

Astronomy in Medieval Europe

Medieval scholars needed to learn the fundamentals of astronomy, and educators like Johannes de Sacrobosco made this kind of education accessible through their textbooks.

Johannes de Sacrobosco’s Book of Spheres

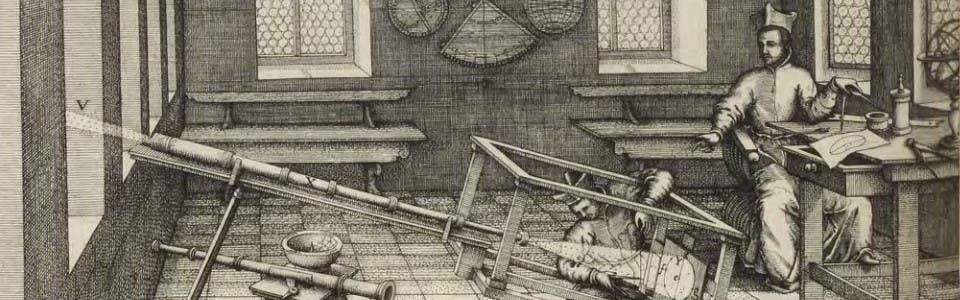

An interesting example in the genre of instructional manuals for astronomy is the Tractatus de Sphaera (Treatise on the Sphere) (ca. 1230) by Johannes de Sacrobosco. The book is not only filled with numbers and mathematical formulas but also with many images aimed at making the abstract graspable. Sacrobosco was an English cleric, astronomer, and teacher. He was born before 1200 and died between 1236 and 1256. Though he only published a few books, each of them went on to become highly popular and influential for several centuries as they engaged with new systems and research in the sciences, for example, the newly introduced Arabic number system or the calendric reform.

The Curvature of the Earth

Because of its success, De sphaera was reprinted several times and used as a textbook in university settings. Contrary to the longstanding myth that medieval scholars believed the world was flat, the book dedicates several pages to establishing the argument that the Earth is round. Sacrobosco uses the movement of the stars to illustrate his theory:

Stellae quae sunt iuxta polum arcticum, quae nunquam nobis occidunt, moventur continue et uniformiter circa polum describendo circulos suos, et semper sunt in aequali di stantia ad inuicem et propinquitate.

The stars which are near the Arctic Polar Circle, those that never set for us, are moved continuously and uniformly around the pole, creating an ‘engraving’ of their circles, and they are always at equal distance to each other and to their neighbours (other star clusters).

Based on the stars’ motion, Sacrobosco determines the direction of the firmament to be East to West. Moreover, he provides a neat argument for the round shape of the Earth:

Quod autem coelum sit rotundum, triplex ratio est, similitudo, commoditas, et necessitas.[…] Unde ad huius similitudinem factus mundus sensibilis, habet formam rotundam, in qua non est assignare principium nec finem.

There are three(fold) reasons for the curvature of the sky: uniformity (probability), convenience, and necessity. […] That is why this sensible world was made “round”; by having this curved form, it is impossible to assign both the beginning and end.

In Sacrobosco’s opinion, it only makes sense for the world to be round – possibly also referencing the religious connotations of the circle shape. The symbol of the circle represents totality, completion, and wholeness, even God himself. Other examples used to support his thesis are the ship sinking away in the distance, and the movements of the zodiac:

After asking the reader to agree that the Earth is round, Sacrobosco moves into different fields of astronomy. Though written in Latin, the book contains many fascinating illustrations and marginalia worth discovering.

Marginalia: Scholars between the Lines – and Spheres

What makes this particular copy of De sphaera especially compelling to a modern reader are the extensive marginalia throughout the book, showing how its owner actively engaged with the text. Although in places indecipherable, this volume shows the human aspect of astronomy, and the marginalia confirm our longstanding fascination with celestial objects. Moreover, the reader’s enthusiastic note-taking suggests that this copy may have been a university textbook.