1610-1700

Galilei, Galileo (1564-1642).

Sidereus nuncius. – Venice: apud Thomam Baglionum, 1610

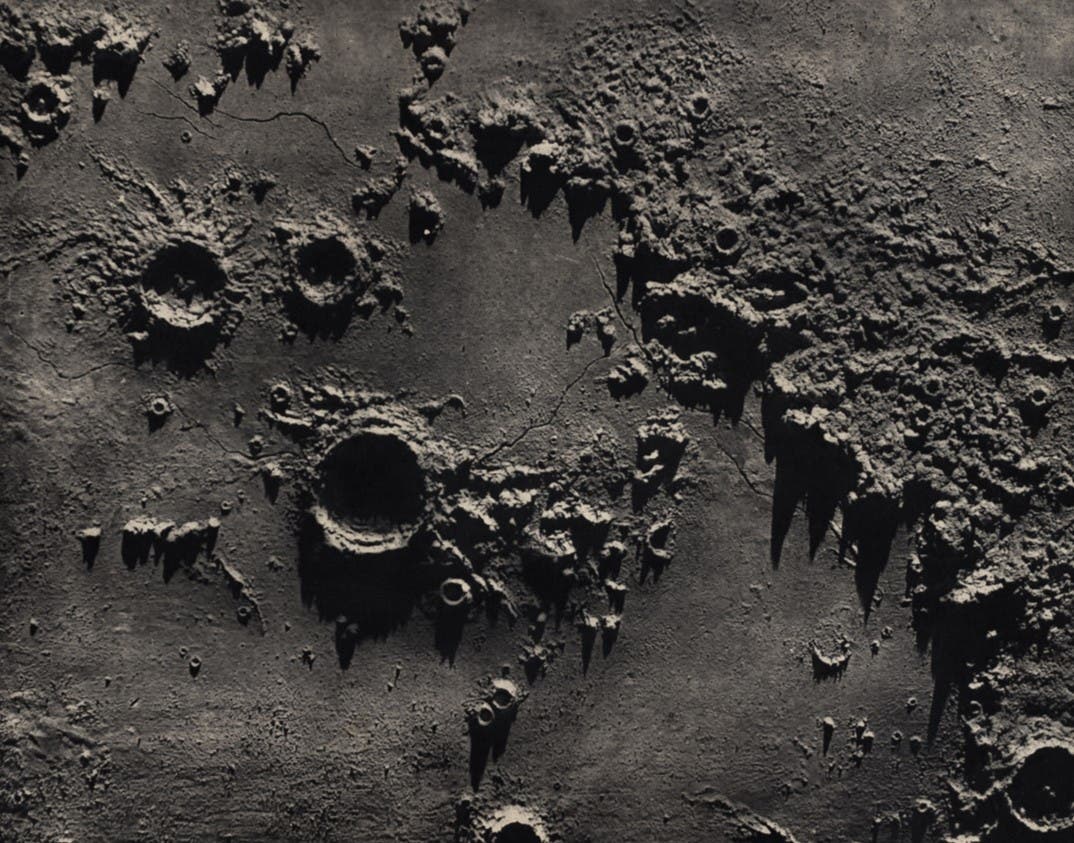

The modern face of the moon first emerged in the early evening of November 30, 1609, when Galileo Galilei in Padua turned his telescope toward the moon, noted the irregularities of the crescent face, and made a drawing to record his discoveries. He made at least five more drawings of the moon over the next eighteen days, prepared careful watercolor sketches from these drawings, and then selected four of these to be engraved for his revolutionary Starry Messenger, which appeared the following March. Galileo's treatise announced to an astonished public that the moon was a cratered chunk of elements --a world -- and not some globe of quintessential perfection. It was a new land, to be explored, charted, and named. The science of selenography was born.

Sidereus nuncius. – Frankfurt: in Paltheniano, 1610.

Galileo's sensational pamphlet quickly reached Germany, where it was reissued in a pirated edition in Frankfurt. In the haste of this surreptitious enterprise, little time or expense was devoted to copying Galileo's careful lunar engravings. Consequently, the Frankfurt edition contains woodcuts, not engravings, much less skillfully executed than the original illustrations. Even worse, the woodcuts are improperly oriented and identified.

None of this would be worth mentioning, except that the Frankfurt woodcuts were the source for the illustrations in most of the later editions of the Sidereus Nuncius, and in many moon handbooks right up to the present day. This has led unwary scholars, who fail to consult the first edition, unfairly to deprecate the Galileo images as crude and unrealistic.